May 24, 2012. Helen Gardiner Phelan Playhouse, Toronto.

May 24, 2012. Helen Gardiner Phelan Playhouse, Toronto.

Against the Grain Theatre has magic that carries even a shoebox production into your imagination and makes it live as art. They did it a few months ago with my favourite opera, the Brecht/Weil Seven Deadly Sins, and they did it again last night with an opera I never much cared for till now, Britten’s The Turn of the Screw.

How did it happen? From the start, the cast seemed convincing, while the production, well, not so much. At a certain point, late into the first act, five characters were onstage singing or reciting different, barely distinguishable tuneless parts against a dissonant chamber-orchestra score reduced for solo piano and BAM!!! the whole thing came together, alive and potent and gorgeous as a Djinn floating out of a bottle.

How did they do it—make the magic happen? My guess is, the company, led by director Joel Ivany, recognized that a production is more a flow of energies than an organization of material parts. In other words, the guiding inspiration for this production is the immaterial element, the music.

The reduction of the Britten’s original chamber orchestra score, entrusted to the brilliant hands of Topher Mokrzewski playing solo on an upright piano, keeps the instrumental energy focused, and somehow, more elemental than the richer full score could be, at least in the minimalist stage exploited by the daring Camelia Koo. This elemental staging quality, supported by ubiquitous wisps of dry ice fog, and Jason Hand’s eerily poetic lighting helps to desolidify the two ‘ghostly’ characters and to translate them, like the music, from the literal world of the stage into the imaginations of both the audience and the other ‘real’ characters. Eventually we are not all sure if they are there or not, but we feel them, like we feel the music.

Britten’s ghostly characters, drawn from a Henry James tale, are Quint and Miss Jessel, servants who, in-life, corrupted Miles and Flora, the two children in their care, and have returned from the dead to repossess them. The protective energies arrayed against the ghosts are an absent guardian, the Governess and the housekeeper, Mrs. Grose.

Flora escapes. Miles exorcises Quint, then dies in the arms of the Governess who is scorched by her failure to protect the boy. There is no redemption as such in the libretto, only disappointment and grim moving on. But the ongoing success of expression in this production brings on a climax for the audience that eclipses the tragic conclusion.

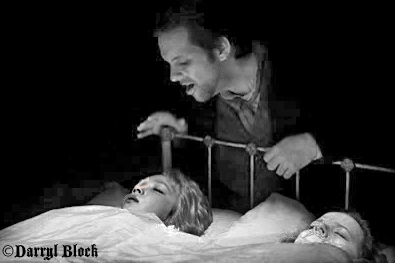

As I mentioned, the cast, all seasoned opera singers, was convincing from the get-go, and what a kick to experience them in the gauntlet between the bleachers never more than a metre or two away, though there were a few moments I would have dialed down some feminine high frequencies. Michael Barrett (who did his makeup?), long a favourite tenor, appeared Beetlejuice-creepy as Quint, and his echoey invocations to Miles remains vivid in memory. Miriam Kahlil, elegantly costumed with bustle by Erika Connor, created a complex Governess, blending warm energy, determination, devotion, doubt and courage into her vocal display.

Betty Alison, also a favourite COC soprano, was a dark and juicy Miss Jessel, spectacularly costumed and brilliantly directed to progress across the stage on her hands and knees like a spider. Another notable directorial touch is when she ‘becomes’ the child Flora, engagingly portrayed with energy and wit by Johane Ansell. Sebastian Gayowsky’s Miles was unique, his part flutily breathed as much as sung, angelic with hints of something a lot more worldly. Meg Latham’s Mrs. Groze was part solid and reassuring, part servile, and part touched by the dark side. A very interesting portrayal.

Against the Grain (AtG) keeps on with the show till May 27. Catch ’em HERE if you dare.

About this review, please leave your comments HERE.

.