Thomas Gannon Hamilton, Panoptic, Aeolus House, 2018, 110 pp. I.S.B.N. 978-1-987872-13-2

… which brings me to your assignment …

“Nobody stuffs the world in at your eyes.

The optic heart must venture: a jailbreak

and recreation.”

~ lines from Margaret Avison’s sonnet “Snow”

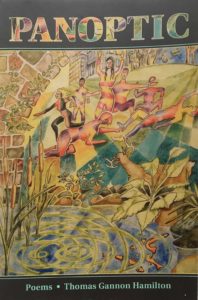

Every book is an artifact, a technology, a delivery system for the work to be found within the covers, and as such first impressions involve an apprehension of and appreciation for those qualities that are particular to the publisher’s attention to presentation. In the case of Aeolus House and Thomas Gannon Hamilton’s book Panoptic the poems within are honoured by the beauty and clarity of production. The cover stock, the paper, and the legible font all contribute to the dignity that these fine poems deserve. The illustrations throughout compliment the poetry. The cover illustration by Hamilton, with its use of Feng Shui, its complimentary combination of water, flora, fauna, and architecture, and its rainbow-colouring of feminine and masculine human figures provides an introduction to the themes we will find within. The opening pen and ink illustration of a swallowtail imago, followed within the book by equally lovely images of catfish swimming tail to tail, and what appear to be mandalas of wheat woven within and emerging from the corolla of a paper flower in combination with Hamilton’s opening epigram “This garden blooms in Fall” combine to prepare us for the delights that will follow when we begin to read. And I can tell you without equivocation that Hamilton does not disappoint. His work is complex without being needlessly obscure, deeply engaged with the world he inhabits and profoundly erudite without being arrogant. The reader lingers, turns a phrase every which-a-way under the light of understanding, sustained by the music that serves the theme, and then is rewarded if not always emerging from the experience unscathed.

It’s a long book, packed with long-line poems, many of which are two to three pages in length, so I’ll concentrate my attention in this review on four poems – the opening poem, the closing poem, the eponymous-to-the-title-of-the-book poem, and the poem that made me laugh out loud so often that I read it and re-read it to amuse my silly self. But then I once coined the question, “What’s the difference between being Solomon, and being Sirius?” so you might forgive my deep appreciation of the truly funniest poem in the book.

The opening poem “Caul” and the closing poem “Mount Pleasant” provide us with something of a framing device in that “Caul” deals with birth and “Mount Pleasant” an apt coda, is a seven-verse contemplation of death and mortality. The alpha poem, rather than being metaphysical is an odd poem concerning a baby born “fully enrobed” in the amniotic sac, a one in eighty thousand rarity. I’m reminded of the star child in Kubrick’s film 2001 when Hamilton compares his own christening to “the first cosmonaut who left earth,/ well in advance of his lift off,/ prior to his re-entry and splash down,/ I had already made my entrance.” The originality of Hamilton’s perceptions and the quirkiness of sensibility enrich the reader’s experience throughout this volume.

In his closing poem he writes: “When you are little you learn to classify/ the living and make distinctions/ between those you’ve seen die;” and you’ve journeyed here if you read this book from front to back, by way of an intelligence that is restless and never satisfied with the obvious surfaces of life. The range and depth of this poet’s concerns remind the reader of the importance of both breadth of knowledge and depth of understanding. He becomes something of a reliable guide directing our attention and illuminating what we see. And what we experience is sometimes achingly sad as he writes of the “untimely death of a lover, best friend,/ husband, wife or someone you love/ no less;” and the journey through grief is equal to the music of Orpheus and his doomed beloved Eurydice. The pain is almost too much to bear. Like Hamlet contemplating Yorick, we are brought to the edge of the grave to think upon “…this ultimate/ enterprise, each holds an equal share,/ all have a common stake; yet/ you distinguish, still you compare.” And I note the way that word ‘yet’ lingers at the line’s end before tumbling to ‘you distinguish,’ and the final words of the closing poem ‘still you compare.’ And is that not the poet’s lot? To compare, to seek a metaphor for the strangest and most mysterious of all experiences – our own mortality. We are born only to die. This need not be morbid or ghoulish contemplation. Like the gravedigger’s comic relief, there are lines in this poem that elicit a smile as it is with the punning of “the grave differences,” leading to a list ‘junior and gramps,/ magnate, minion, maven, twit” and so on. The wit in these lines does not go unnoticed. And the rhyming of “twit” with the phrase “pulses quit,” disallows the reader from descending into a dark mood commensurate with the overplaying of morbidity.

In the title poem, “Panoptic” I am reminded of Avison’s importuning of the reader to fully engage the world in her sonnet “Snow.” The idea that in order to understand and appreciate experience, the individual must engage in active cognition, “Nobody stuffs the world in at your eyes,” she writes, and Hamilton’s opening salvo in his poem “Diminished as I am in your ears,/ I cannot get between them,/ enter and leave without a hearing,/ the way rodents and roaches cross/ more freely than thoughts,/ from one cell to another.” The word ‘panoptic’ is all by itself an invitation to engage. And the poem ends with an echo reference “Though diminished in your eyes,” as the opening line in the last verse. Understanding these lines is not easy work, but wrestling with them is damned rewarding play. Like Avison, Hamilton rewards reading and rereading. The music sustains and the effort rewards.

And then there’s the quirky “Home Ec.” A poem in which the speaker is a teacher and the reader is privy to the reactions of an imaginary class wherein we are invited to contemplate the joy of cooking squirrels, rabbits, woodchucks, opossums, beavers, raccoons, bears, and finally humans. And the teacher chastises the imaginary class, like that in Monty Python’s sex education class in their film The Meaning of Life. To give but one example: “Seminoles who tasted settlers, runaway slaves/ and their own, reported some differences;/ alright, that’s enough, go stand in the hall.” (Ialics are mine). The poem ends with “and now for your assignment,” and so I end this review by suggesting to the reader of this review “and now for your assignment” read Panoptic and then see me after class. To order your copy, send $24 ($20 + $4 p&h) payable To Tom Gannon Hamilton, 577 O’Connor Dr., Toronto, Ontario, M4C 2Z9.