May 9, 2012. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto.

May 9, 2012. Roy Thomson Hall, Toronto.

John Corigliano’s Clarinet Concerto generates tremendous excitement. The writing and instrumentation are so original that you cannot anticipate what’s coming; but the changes always surprise by their rightness and beauty. Corigliano consistently delivers the pleasure of the unexpected.

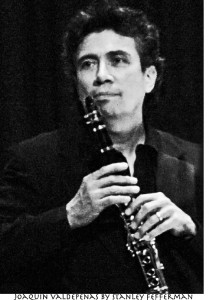

The composer himself must still be excited by this work which premièred in 1977, because he travelled here to introduce Joaquin Valdepeñas performance of it with the TSO, Peter Oundjian conducting.

There are three kinds of homage built into the work. The first movement, entitled “Cadenza,” is an homage to the virtuosity of Stanley Drucker, principal clarinet of the New York Philharmonic whose performance of the opening cadenza—150 notes played with 1 breath—Corigliano compared to the breaking of the 4 minute mile. Valdepeñas accomplished that and every other virtuosic challenge with ease, and also impressed with his extraordinary tone, warm and smooth as human flesh.

The second movement, entitled “Elegy,” is an homage to the composer’s father who was concertmaster of the New York Phil for 26 years. Unaccompanied violins introduce the slow, sad, clarinet solo of exquisite beauty, stirring the lower strings to spread a deep, Brahmsian moan. The music floats and drifts into a dialogue between clarinet and solo violin played by Mark Skazinetsky. The movement concludes by rounding back to its beginning.

The third movement, entitled “Antiphonal Toccata” opens with a quote from a piece by Giovanni Gabrieli (1597). Corigliano drew on Gabrieli’s brilliant use of antiphonal instrumental choirs arranged for effect all around the performance space. Thus onstage conversations between solo clarinet and onstage brass—trumpets and trombones are answered by brass players situated offstage, side, centre, and rear of the hall, echoing and re-echoing lines of a descending canon.

The effect is an exuberant pandemonium, with the conductor at its centre, going all Prospero, stabbing his wand into the air towards a circle of minions in the space above him who release sonic bursts at his command. The audience, roused by the challenge of this music, rose repeatedly to its feet to offer ovations.

The music after intermission offered comfort after the earlier challenge: The Planets, by Gustave Holst (1920), recently recorded by Oundjian and the TSO. This is program music, fun to follow: fanfares and martial airs develop into menacing assault of drums—the planet Mars; a horn theme rippling out ever expanding liquid rings of warmth—the planet Venus (with lovely work from cello and celeste); Mercury, jaunty and fleet as Morse code, sets pulses running; Jovial Jupiter, a parade of clowns swelling into a much repeated anthem to collective joys; the low groans and tolling chimes of Saturn, bringer of sour old age; the urban swagger of streetwise Uranus the Magician; and twilight zone tones of Neptune, the Mystic.

To go back to the very beginning of the concert for the evening’s most memorable single moment, that would be when the stage-lights and house-lights dimmed out the orchestra and all the patrons. Spotlights above the stage revealed 8 brassplayers, 4 in each choirloft stage-right and stage-left. They performed Gabrieli’s Canzon per sonare No. 27, an antiphonal work redolent of antique heraldry. Very tonic.

Please leave your comments HERE