Sunday, April 3, 2011. Glenn Gould Studio, Toronto.

The theme of Amici Ensemble’s final program for this season, entitled “In the Shadows” is good music by composers who are now overshadowed by composers who wrote great music. Beethoven wrote great music. Louis Spohr wrote good music, was as famous as Beethoven for a while, but was largely forgotten except for a few ‘good’ pieces that people still like to hear.

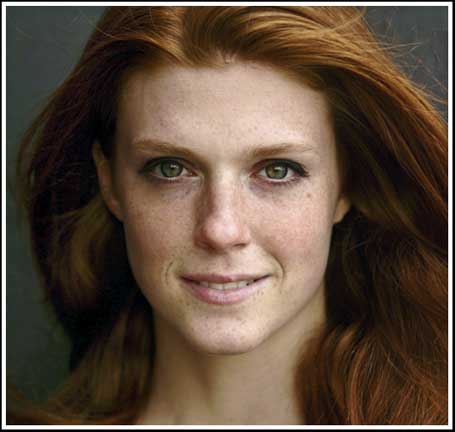

Wallis Giunta sang Spohr’s Six German Songs, Op. 103 for voice, clarinet and piano. Ms. Wallis’ voice has authentic presence, which she blended with the voices of Amici’s Joaquin Valdepeñas’s clarinet and David Hetherington’s Cello. The music they made together flowed in muted colours reflecting lyrics that lament love that cannot be expressed, love that cannot be attained, love that can be enjoyed only in dreams.

The performance was beautiful, the songs are settings of über-sentimental German poems, and it’s a bit beyond me why people would still be interested in putting fine energy into outworn poetic and musical ideas. But that’s kind of the point of the program: some music keeps hanging around precisely because it never pushes the musical envelope—even of its own time, and classical music audiences, by nature and nurture conservative, tend to like falling back on a bit of easy-listening music.

The Beethoven piece that cast a large shadow was Twelve Variations on the theme “Ein Madchen oder Weibchen” from Mozart’s Opera “The Magic Flute,” Op. 66, for cello and piano. It has the youthful, quirky, horny, unpretentious energy of Mozart’s Papageno in it, and the creativity of a young Beethoven experimenting fearlessly with one of the popular tunes of his day, pushing the envelope by arranging it for the combination of piano and cello which was almost unheard of in 1796. Serouj Kradjian’s spring-loaded piano makes this music dance in tandem with the rich flow of David Hetherington’s cello.

After intermission, Anton Webern (1883-1945) was the giant chosen to cast his shadow over music in early 20th Century Vienna. Webern, along with Schoenberg and Alban Berg pushed European music out of the tonal envelope into 12 tone territory. His early work, Three Little Pieces Op. 11 for cello and piano (1914) was by far the most interesting work on today’s program. Webern’s opus is astonishingly concise and concentrated. Although not yet fully 12-toned, it is music without repetition of pitch or sonority, and the three movements are so short they need to be measured in seconds: 69″, 21″ and 62″ respectively. Nonetheless they rivet the attention, refresh the mind, and bring about a meditative sense of rest.

Carl Frühling (1868-1937) wrote Romantic music, was forced by economics to spend most of his time as an accompanist, and died obscurely in poverty. Most of his music was lost. Frühling’s Trio in A minor for Clarinet, Cello & Piano, Op.40 was rediscovered about 10 years ago by cellist Steven Isserlis. The Amici Ensemble was among the first to record this work, which is so well-made, and despite being ‘unfashionable’ is very beautiful, especially for the melodic themes of the first two movements, and throughout for the rich orchestration of Frühling’s Brahmsian style. It’s really only in the final movement, so symmetrical, balanced and elegant, that one gets a sense of decay, — the sentimental attachment to the dying style of “Vienna before de Vore.” That said, my recording of Frühling’s Trio has a few more listenings in it.