March 6, 2012, Jane Mallet Theatre, Toronto.

March 6, 2012, Jane Mallet Theatre, Toronto.

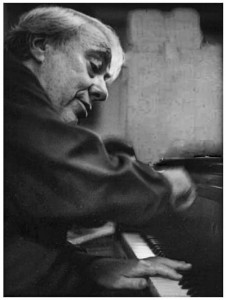

Richard Goode chose three collections from Schumann, Chopin, and Brahms for his Toronto program. Short pieces make easy listening, and 26 of them offer the charm of variety. This survey of Romantic melodies promises the pleasures of the familiar, but Goode delivers excitement in the unmistakeable boldness of what has been called “the intensely-pondered quality of his playing.”

As if to understate the star quality of his performance, Goode performed on a dimly lit, shadowy stage. The opening passages of Kinderszenen (Schumann, Op.15) had a leisurely glow, as if Goode were playing for himself alone. The second piece, the sprightly “Of Strange Lands and People,” picked up the pace, but without a hint of showiness. One felt the spontaneity, but bounded by Goode’s own reasonableness. As the work developed, a sense of the “story”, began to emerge from Goode’s shaping of phrases. The ever-lovely “Traumerei” spoke not only of the pleasures of reverie, but also about the passage of time with a sobering wistfulness and, surprisingly, humour. That said, he did not neglect the sparkling, spinning, spooky colours of the work.

Brahm’s late Seven Fantasias Op. 116 (1892), is, by contrast with the early Schumann, old guy music, though it doesn’t appear that way from the start. The D Minor Capriccio explodes in a show of kinetic drama that rags around like an old-time-movie chase. However, the A Minor Intermezzo (Andante) follows with tentative steps, broken melodic progressions in which the lyricism is querulous and tinged with the tragic. The G Minor is a passionate declaration of love, insistent, manic, rhapsodic, tempered by the E (Adagio) in which quiet, reflective gentleness and a darkening drama prevail. The E Minor keeps the slow pace but adds a note of ironic humour in a kind of cakewalk, which qualities darken more in the following Intermezzo. The work ends in a D Minor Capriccio that is fast, furious, with sudden change-ups that lend an ominous quality to the final richly textured moments.

After intermission, Goode presented six Chopin miniatures from the 1840’s: three Waltzes, a Nocturne, a Scherzo and a Ballade. The singing quality of Chopin’s lines were enhanced by Goode’s mumbled vocalese, and by his total lack of interest in playing the virtuoso or the nationalist. Instead Goode offers a kind of masculine gravity, a gentleness marked by deliberation and restraint so compelling that the audience could not hold back their applause after Scherzo No. 3 in C-sharp Minor, which Goode acknowledged by rising and bowing. He then styled the frothy, theatrical Waltz in A-flat with a classical grace, and let the fleet Waltz in A-flat Major lift off in a dizzying whirl that again lifted the audience to their feet. The Ballade No.3 in A-flat Major concluded the recital on a romantic, sort of popular note, and in the several encores, especially the Scherzo from Beethoven’s Op. 31, No. 3, Goode shared a wild humour that was without any cares at all.

Please leave your comments HERE.