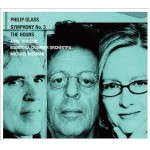

Philip Glass. Symphony No. 3, The Hours, OMM, Harmonia Mundi, 2013.

Philip Glass. Symphony No. 3, The Hours, OMM, Harmonia Mundi, 2013.

Philip Glass has his own record label, Orange Mountain Music, dedicated to archiving all the recordings the composer has made over the last 30 years and counting.

The label’s latest project brings together several award-winning energies. Glass’ filmscore, The Hours (2003) received Golden Globe and Academy Awards nominations for original filmscore, and was the British Academy winner in that category.

Michael Riesman, pianist and the Glass Ensemble musical director who has produced most of Glass’ soundtrack recordings, arranged the score of The Hours into a three-movement concert suite for piano and orchestra which he has played in halls around the world with major orchestras.

The current recording has Riesman playing The Hours with the Manitoba Chamber Orchestra conducted by its Music Director Anne Manson, highly esteemed for her work in opera. Under Manson’s baton, The Hours gets to tell a story that rises to the heights of grand opera and descends towards popera and soapopera.

Manson modulates the florid space of the score to allow Reisman’s piano to make its own melodic way. Her control of dynamics is extraordinarily imaginative. Sometimes the piano’s voice stands out from the orchestral flow—at times, especially in the first movement, sounding a bit shrill for my taste.

At other times, the piano sinks deeply into the music’s musculature and rolls like the rib-flow of a dragon’s skeleton. At times it sounds like a heart-beat; then it emerges to the sonic surface like colourations on the hide, and articulates further into spines, feather, wings, legs, and at its grandest heights like a locomotive’s driving rods. In the final passages the ripples of Riesman’s piano tapers off so portentiously you think it’s going to come back. But it doesn’t.

Philip Glass’s Symphony No. 3— a symphony for strings that showcases all the string-players individually, was premiered in 1995. The moderately paced, quiet, opening movement is Glass: it throbs. The pear-shaped tones of Manson’s dynamic lines swell and attenuate in a dialogue of substance and shadow.

The second movement gallops in on a horn-like orchestral blare, loud and strident. Compound meters in unison and multiharmonic textures disport themselve like Baroque figures in a Vivaldi Concerto. Then the flow goes some towards the Middle-East, then pulses Westwards into the vernal celebrations of Carmina Burana.

The third movement introduces an hypnotic chaccone for cellos and viola, adding voices till it ends with a solo violin’s long, passionate complaint. The short finale dances towards the Baroque figurations of the second movement, chugs in chromatic rhythms back to the opening movement’s melodramatic, operatic dialogue, deeply dips into a Spanish descending arpeggio, and after a flurry of celebration, fades away.

Philip Glass’ music has a sound of its own: if you like his sound, this album, recorded in the CBC’s Glenn Gould Studio, is a sweet spot for listening.